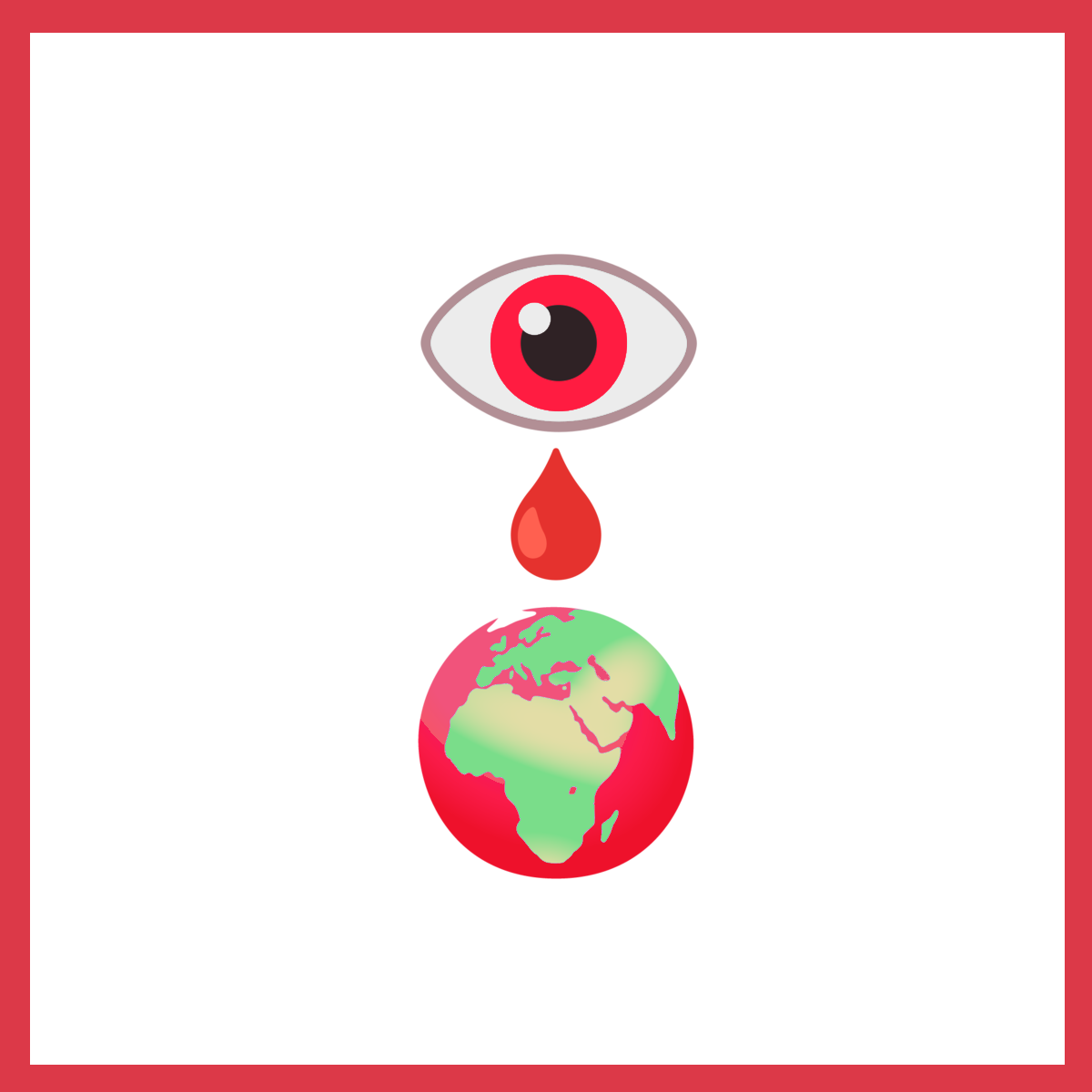

01 Feb Monochromatic Divine Vision

God does not see in black and white,

God sees only the color white

Latent or shrouded in our own darkness.

He wept bloody tears to wash out the shade.

My upcoming book, Ghosts in Our Doctrine, centers not on a refutation of a solitary theological issue, since in many regards these derive from other more epistemologically primary topics. Rather, I wish to examine a reality-defining locus and how it anchors our language and ways of thinking. The convertibility and notional distinction of being, truth and goodness is ultimately one of the landmark achievements of philosophy, since it defines our most primal natural knowledge (I am, I am thinking, I am intending) as well as terminating as an analogue to the Trinity. While I gage this concept in a limited scope, to wit as it “cashes out” in the first and second creation, I thought it might be helpful to delineate how this doctrine underpins common modern errors.

Imagine first the distinction between reality, truth and use as we understand them in science: ontology, epistemology and ethics. The ontological governs the epistemological and the ethical. The relationship between epistemology and ethics is almost entirely routed through ontology with some dependence of ethics on epistemology. In addition the ontological is tied to the other two as they relate to our ability to intellect and will what is. Structurally speaking, epistemology examines how we can know, and ethics dictates what we do.

Imagine now the distinction as these are understood substantially — what we could describe as “how God understands them.” There is no distinction between reality, truth and use because these latter two must relate an intellect and will back to reality. We cannot ground the distinctions outside of an intellect and will, so there is no extramental and extravoluntary reality to situate truth and goodness. That is, there is no truth without cognition, and no goodness without volition. There exists truth and goodness tout court given a grounding cause, i.e. God, but in a cosmos of rocks and stars and not much else, there is only the per se. “God sees only the color white.”

Should we dismiss the intrinsic relationship of being, truth and goodness, or otherwise dismiss notional distinction, we immediately lose the possibility of a transcendent Deity, since the simplicity of God would be impossible if it were required for God to be composite of powers. That simplicity is required for the indeterminateness of God, which is a feature of a grounding cause for contingent things. Contrariwise the lack of distinctions between the three make it difficult to assert a distinction between God’s relationship to the cosmos and our relationship to it.

The destructive capacity of this line of thought is not simply in the obscurity of a God not evident of to our senses, but the annihilation of any coherent situating of the three transcendentals. If we take the three to be univocal or synonymous, to wit that our comprehension of reality is the same as the object of our thought, we enter into a world that is functionally the same as a board game, where probabilities have an ontological presence in things (like how movement in Monopoly is contingent on actual probabilities in a dice roll) and evil is a substance contrary to good (like chutes in Chutes and Ladders which only exist to obstruct our desired end). The alternative is a world of disconnected appetites, consideration and reality, which is not unlike a badly written novel where decisions are made on the whims of the author (creating situations that don’t make logical sense) and our expectations about a state of affairs are either misconceived or actively thwarted (fooling the audience and doing so badly enough that they can see it).

While arguing that modernity is the misbegotten child of this error is a more monumental task than I care to tackle, it suffices to conclude that given our experience within modernity, many of its irritants can be at least assessed according to its debauched framework, designed in contrast to our doctrine of convertibility. We have tried to see through the eyes of God, and have only succeeded in deluding ourselves: that what we see is what God sees, with all its perfections; or that God sees is what we see, in all of its flaws.